Game Changer: The Atlantic Philanthropies

Resource type: News

Generosity | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

By Nicole Richards

Christopher G. Oechsli, President and CEO of US billionaire Chuck Feeney’s The Atlantic Philanthropies on why philanthropy is a force multiplier, the difference between ‘venture’ and ‘adventure’ philanthropy, and lessons learned from a limited life foundation.

“It’s a real honour to talk about a fellow who is my hero and Bill Gates’ hero. He should be everybody’s hero.” So said Warren Buffet in June 2014 while presenting the Forbes 400 Lifetime Achievement Award to The Atlantic Philanthropies founder, Chuck Feeney.

“It’s a real honour to talk about a fellow who is my hero and Bill Gates’ hero. He should be everybody’s hero.” So said Warren Buffet in June 2014 while presenting the Forbes 400 Lifetime Achievement Award to The Atlantic Philanthropies founder, Chuck Feeney.

Established in 1982, Atlantic Philanthropies is both the embodiment and realisation of Feeney’s Giving While Living philosophy. The limited life foundation is tasked with disbursing an estimated US $7.5 billion of its founder’s fortune to bring about lasting change in the lives of disadvantaged and vulnerable people before its last grant is made in 2016. Atlantic’s doors will close in 2020.

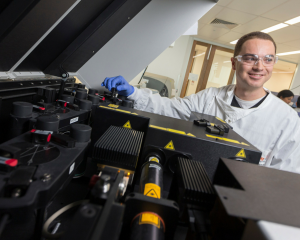

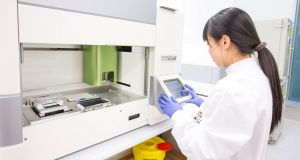

By the end of 2014, the foundation had granted more than US $7 billion in areas spanning ageing, children and youth, population health, reconciliation and human rights across five continents, including Australia. Here, grants totalling more than AUD $570 million have helped universities and health research institutions establish or expand 25 biomedical research facilities in four states. Additional funding leveraged from government and local philanthropy brings that total value even higher.

Here, Atlantic President and CEO, Christopher Oechsli, who will visit three Australian cities this month to participate in 11 events arranged by Koda Capital, shares his insights and experience as leader of one of the world’s most intriguing philanthropies.

Generosity thanks David Knowles and Chris Wilson at Koda for helping to facilitate this interview.

NR: Atlantic Philanthropies has been lauded as having “changed the culture of Australian philanthropy.” As a game-changing funder, what have been the most valuable grant making lessons the organisation has learned after working in this space for more than 30 years across five continents?

CO: Begin with work on things you know, care about and can learn about. Be a student. Observe and listen before you act.

Assess opportunities as investments. Aim for impact in areas of interest. What are the evident needs and conditions in each context? What might desired success look like? Is it achievable? If it’s a long-term, seemingly Sisyphean effort – like research or efforts to advance rights or health – are there achievements or appropriate milestones that can offer evidence of progress towards desired longer-term outcomes?

Each country, community and context is different and presents its own opportunities and challenges to grantmaking. Perhaps the most valuable lesson is the one that might seem obvious: Find the best people to work with; people who know the local landscape as well as the big picture; people who can navigate the sometimes choppy waters of government and politics, funding and philanthropy and trust their instincts, talents, dedication and leadership to guide the work to success.

Modesty and humility are essential. Effective philanthropy cannot be about the donor. It has to be about the grantees and their work. The grantees and beneficiaries in the community are the primary drivers of the work. What they can achieve, with support from Atlantic or other funders, should be the measure of success.

Responding intelligently to what communities need instead of imposing what a donor thinks they need is a good rule of thumb, though it can be helpful for donors to challenge what’s possible and encourage people to think big. Providing resources certainly makes bigger thinking possible. Developing leverage and partnerships with government, as has been done very effectively here in Australia both at the national level and in the states, helps sustain projects and programs and increases the likelihood of future support. Government budgets are larger than those of all foundations combined, and government support is one reflection of public support.

NR: Forging new (often unprecedented) partnerships between philanthropy and government to leverage additional funding has been a hallmark of Atlantic Philanthropies’ work. What is your strategy for engaging governments around the world and why are these partnerships so important?

CO: Government is an important audience, partner and sustainer for a lot of the work we do. If you want to leverage resources and effect change, you have to work with government to magnify and sustain the effort.

At Atlantic, we have learned over the years that philanthropic investment, if done right, can be a force multiplier. Investing strategically in worthwhile causes and programmes not only strengthens communities and leadership, enhances rights and social services, and offers opportunities to the disadvantaged, it also provides space – both physical and conceptual – to live, imagine, innovate, invent and learn. It also can leverage a shared vision through additional funding and partnerships that will carry the work forward beyond the scope and scale of any individual funder’s grantmaking.

In Australia, as in several other places, Atlantic’s partnership with government has been essential to the development and execution of a shared vision of a more vibrant research and learning capability and a resulting knowledge economy. When our founding chairman, Chuck Feeney, first proposed in the 1990s that Atlantic invest in The University of Queensland to build a molecular bioscience institute, our funding was quickly and eagerly matched (and exceeded) by both the Queensland state government and Canberra.

Since then, Atlantic has funded 25 educational and research facilities in Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania. These facilities could not have been built and their work sustained, without both government support and support from the institutions’ leaders and donors. If there had not been local interest to build a knowledge economy, and develop a Smart State, foundation investment would not have been nearly as successful.

The medical, research and academic institutions and facilities that Chuck and Atlantic invested in underpinned and complemented the interests of local and national governments to promote the discovery and delivery of new knowledge and breakthrough research to improve health for entire communities, states, and nations.

Similarly, Chuck and Atlantic catalysed co-investment with the Irish government to support higher education and advanced research in the Republic of Ireland (known as the Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions, or PRTLI). It is one of our hallmark initiatives and, through 2014, Atlantic’s own $262 million towards the program has leveraged more than a fivefold investment by the Irish government. The combination of alignment and challenge achieved lasting impact and reach, and has helped build and sustain an Irish knowledge economy.

In Northern Ireland, Atlantic’s funding of shared education, dementia care and early childhood learning has leveraged investments of more than $53 million in these fields from Stormont, Northern Ireland’s legislature.Using our grants to leverage government investments and longer-term enabling policies has become part of Atlantic’s standard protocol. We have also used this approach to great, lasting effect in Viet Nam and South Africa, where we have partnered with governments to strengthen the role of primary care and nursing within health systems to improve health outcomes in historically under-resourced and disadvantaged communities.

NR: In Atlantic’s work to reduce “inequality of opportunity” you’ve suggested two key factors are required to catalyse change: evidence and a change in narrative. Given the increasing emphasis on data to measure outputs and outcomes in philanthropy, how can we broker and evaluate cultural narrative change?

CO: Most of us believe in the fundamental aspiration of fairness – giving people a fair shot and reducing unreasonable barriers to opportunity. Evidence and narrative change are collaborative efforts to influence minds and hearts, respectively, to achieve these ends. Evidence is critical to identifying a problem and designing effective responsive solutions. But if you’re trying to achieve systems change to enhance fairness in practice, you have to reach both influential and broad audiences with stories that motivate, that bring home in more visceral, human and resonant ways, why change is necessary to achieve fair opportunities and outcomes and why it is worth caring about.

Changing narratives, particularly those that negatively affect the rights, representation, opportunities and advancement of the marginalised and vulnerable – whether ageing members of society, migrants with little to no legal protections, or those living with the lingering legacy of discrimination and violence due to the colour of their skin or whom they love – doesn’t come easily or quickly. There have been huge victories recently in both Ireland and the United States to cement equal rights for LGBT people. It is undeniable that these tectonic shifts in government policy would not have been possible without years of hard work demonstrating a different, positive vision of society and bringing public hearts and minds along.

Narrative change to reframe privilege, power, divisiveness, bigotry and uninformed arrogance is a long game, and one we are deeply interested in. As a limited life foundation now nearing the end of our grantmaking, we still see ourselves making meaningful contributions to longer-term challenges. Investments in education – defined broadly as efforts to engage the public in thoughtful consideration of meaningful issues – to change attitudes and combat biases are vital. We remain confident that the arc of the universe continues to bend toward justice – but, as Dr. Martin Luther King reminded us, that arc is long.

NR: Ford Foundation’s recent decision to focus solely on addressing inequality and Darren Walker’s comments about the need to shift not “what” Ford funds but “how” it funds have created quite a buzz. Do you think fundamental systems change for philanthropy is on the horizon? Do we need greater philanthropic investment in areas such as research and advocacy to achieve heightened impact?

CO: Darren (Walker) is doing great things at Ford with his increasing focus on inequality, a defining issue of our times. And we agree that certain approaches to funding (the “how”), such as significant, longer-term core institutional funding, can be more effective than short-term project funding. We also live in a time when more and more philanthropists and donors – especially those emerging from a younger generation than Chuck Feeney, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett – are looking to the Giving Pledge and Chuck’s even more immediate philosophy of Giving While Living, to guide their philanthropic investments. Those phenomena – of people deciding to give their considerable means at an earlier stage in life, and the growth of “limited life” philanthropy – represent a significant change in approaches to philanthropy.

Young philanthropists who have made huge fortunes by providing technology solutions seem ready now to take their same can-do, big bet, system-changing attitude to solving major issues. We applaud that entrepreneurial, strategic approach, which is so similar to Chuck Feeney’s philosophy about philanthropy. But Chuck also has emphasised that he and Atlantic learned a lot along the way. Don’t assume that success in business makes you immediately effective at social change and philanthropy. You have to learn and work at it. It’s not easy, but starting sooner, gives you a leg up on the learning curve.

Atlantic has invested heavily in both research and advocacy; and we have long acted on the belief that the greatest impact comes by changing systems at their root – with evidence from research and motivation through advocacy – by addressing causes of problems rather than their residual effects, so we support funding approaches that best achieve that.

In social sciences, as in natural and life sciences, you have to spend time understanding the problem to design appropriate solutions. Investing in research – scientific and biomedical research to get at the root of disease and social science data and research to get at the root of big, multifaceted, knotty systemic challenges like “inequality” – and in advocacy to motivate and speed system change are two approaches we have taken and will continue to take with our culminating grantmaking.

NR: “Big bet” philanthropy is something that Chuck Feeney has referenced many times. How vital is risk to effective philanthropy?

CO: Like most philanthropists of the past, and like the new tech entrepreneurs now turning to philanthropy, Chuck Feeney was first successful in business. Anyone familiar with his approach to investment knows that he is an informed risk-taker, perhaps more accurately a well-equipped prospector with big vision. Chuck is known to say: “Think big.” That is an inherently risky proposition.

Taking risks makes sense when it makes sense to take a risk, not making risky decisions for the sake of excitement or novelty. Chuck is a venture philanthropist, not an adventure philanthropist. He observes, reads, learns and interacts before he acts. Is there a worthy opportunity? Is the upside value good, the prospects achievable? Are the leaders dynamic, do they have strong values, big hearts, big vision and the perseverance and diligence to achieve their goals?

Identifying undervalued and underappreciated opportunities, initiatives and institutions has always been part of Atlantic’s DNA, born from our founder’s own protocol. From Limerick to Belfast, Cape Town to Queensland and Huế to San Francisco, Chuck and Atlantic have often embraced these undervalued opportunities and taken the long view with some big bets. And many of our grantees’ biggest achievements have been born out of the visionary and informed risks we have taken with them along the journey. But yes, big bets are inherently risky, and good bets are a good risk.

NR: As President and CEO of an organisation that is both charting a new course in global philanthropy and working to achieve goals against a ticking clock, what have been your greatest leadership challenges?

CO: Although it has been called so, Atlantic is not a “spend-down” organisation – we have, in fact, ramped up our investments substantially in targeted Atlantic themes in these final few years as we commit our last sums. Selecting and designing our final work and that of our grantees to have lasting influence and impact long after we’ve left the philanthropic field is perhaps the greatest challenge. There are easier ways to conclude, but they may not necessarily yield the highest and best use of our funding.

We want to finish well and with lasting effect, and we have thought long and hard about how to do that. As a result, in addition to making a few big bets on what we refer to as “champion,” proven, catalytic organisations, we are developing some very limited final big investments in longer-term leadership and human capital development in themes that both reflect Atlantic’s historical experience and pose great challenges in the 21st century. These include themes of health equity, inequality and democracy, a healthy ageing mind and racial equity. Chuck and Atlantic have always invested in and bet on dynamic, visionary leaders. We hope our final investments will generate more of these individuals but in ways that encourage them to be engaged in sustained communities of learning and action. We’ll be rolling these out in our final months of grant making.

One fundamental challenge to ending well is having to say “no” to so many worthy ideas, needs, opportunities and people. That’s a hazard of philanthropy, in general, but as we conclude our work this aspect has intensified. It is difficult and consuming, but necessary, to be respectful of the people who approach us with compelling ideas that we simply cannot take up if we want to remain focused and effective with our remaining finite resources. Some people understand and acknowledge this difficulty well but to others we – I – may seem short-sighted, even arrogant.

Another challenge is to transition our employees, as we reduce in size, from the unique experience at Atlantic to their next professional opportunities. These days we’re saying goodbye to extraordinary people every six months and it is always difficult. We are enthused and inspired, however, by what many of our “graduates” move on to; and we work at supporting some of those opportunities with transition fellowships.

Lastly, and most poignantly, our Giving While Living work is a reflection of our individual limited lives. What are we here to do? If we have earned wealth, to what effect is it to be deployed? We want – Chuck wants – wealthy individuals to think about what wealth is about and what it means to have and use that wealth in our short time on Earth. My own challenge – one Chuck has implicitly bestowed on me – is to make that a promising and accessible challenge to others of means and ability who have a disposition to improve our shared world.

NR: What do you consider Atlantic Philanthropies’ greatest achievement/s?

CO: First, it’s critical to recognise that what we’ve done is to help create resources and conditions that will allow our grantees to succeed and thrive. We’re a funder and strategist in partnership with grantee organisations and governments. We hope we add value and support, but they do the hard work and deserve the credit.

Second, what we hope may be our greatest achievement is to reflect how big bet, limited life philanthropy can make a difference – that Giving While Living is both a satisfying and effective approach to deploying philanthropic monies to their highest and best use.

To do this, we will compile proverbial “playbooks” for the burgeoning list and new generations of donors who embrace Chuck’s philosophy of Giving While Living and “limited life” philanthropy. That achievement is also an obligation, as the largest and most far-reaching foundation by far to be ending intentionally, to help others learn from and decide whether and how to apply our experience to their own philanthropy.

But getting beyond spreading the wisdom of Giving While Living – that concentrating one’s giving during one’s lifetime and learning from one’s mistakes and adjusting quickly – allows for great impact. However, what has been most remarkable has been balancing funding partnerships with government in many places with supporting local, citizen-led organisations that hold government to account.

Still, these are some of the big achievements and big bets that first come to mind:

- As mentioned previously, the development and growth of research in third-level institutions and the knowledge economy in the Republic of Ireland

- Over $2.6 billion dollars in capital investments, leveraging many billions more to create built environments for those who create and innovate

- Helping create a Smart State in Queensland and fostering exponential growth of biomedical research and discovery across Australia

- Development of a national public health system in Viet Nam, through investment in local public health initiatives and facilities

- Providing support for guaranteeing the constitutional promises of equity, rights and justice, and the promotion of better health care and service delivery (notably TAC), in post-apartheid South Africa

- Advancement of the peace and reconciliation processes in Northern Ireland, as well as making great strides in shared education, dementia care and early childhood learning to improve government services and reduce sectarian disparities

- School discipline, near universal healthcare coverage and clear movement toward death penalty abolition in the United States

- Highlighting the use of strategic litigation and advocacy funding to shape public and government policy, the fruits of which can be seen in outcomes such as South Africa HIV treatment and education policies; Irish policies on ageing and dementia; implementation of the Affordable Care Act in the United States; a changed relationship between the US and Cuba.

Research images courtesy Diamantina Institute, The University of Queensland.