Up Close: Blogging from South Africa

Resource type: News

Gara LaMarche and Jack Rosenthal |

Night and a Day in Queenstown

Posted by Gara LaMarche | 18 March 2011, South Africa

As Jack has chronicled, we arrived in Queenstown, the final leg of our journey in the Eastern Cape, in the dark, around 7 p.m. This was a problem for two reasons. First, we’d been warned that we ought to complete our two-hour drive from Grahamstown – mostly through beautiful, depopulated rural areas that remind me of my years in Texas – before nightfall, so as not to hit wild animals crossing the road like the huge, elk-like kudu that are for some reason drawn to headlights. In a battle between Avis SUV and kudu, the latter is likely to win. Those of you who are aware of my lack of affinity for non-domesticated animals will appreciate that I did not find this a relaxing drive, however scenic. Second, as Jack has noted, when we arrived at Queenstown, a power outage had darkened half the town, including our guest house, so we spent a good deal of time trying to find it in the rain. When we finally got there, our rooms were lit by kerosene lamps.

We managed to make it to, as Jack has noted, a lovely home-cooked dinner at the home of Patrick Pringle, the director of the Queenstown Rural Legal Centre (QRLC), an Atlantic grantee working with poor communities on the Eastern Cape to stave off illegal evictions of farmworkers and assist with the myriad other legal issues of people too poor to afford lawyers for marital, estate, labour and other matters. Patrick grew up on a farm in the Eastern Cape, went to law school, worked for a mining company, and then shifted to public interest work, first with the Legal Resources Centre in Johannesburg and then returning to the province of his birth to head up the QRLC, which is associated with Rhodes University, where we visited yesterday. His wife Kathy, a speech therapist and counselor, and their daughter Janet, on a visit home from India, served a splendid roasted free-range chicken and potatoes and home-baked desserts.

When we spent time with Patrick and his staff – both credentialed attorneys and “candidate attorneys” serving their apprenticeships with the agency – over lunch at his office today, he told us that AIDS continues to cut a devastating swath through the community. “If you walk down the street in Queenstown,” he said, “it’s likely every third person you see will have HIV.” Among other things, this fact has an impact on their work to protect farmworkers’ meager estates, as a “generation” in many families has come to be as short as ten years.

The first part of our day was devoted to Atlantic’s Health Programme grantees, both of whom we met at Frontier Hospital, the primary medical facility in that part of the Eastern Cape. About 25 stakeholders from the province health district, the hospital, the nursing college and our grantee, the Fred Hollows Foundation, gathered in a conference room for a discussion of the Atlantic-supported effort to eliminate unnecessary blindness among the poor people of the Eastern Cape. It was led by the local Fred Hollows director, Mary Hlalele. Atlantic Founder Chuck Feeney made the first grants to the Fred Hollows Foundation, named after a visionary (pun intended) Australian eye doctor, skilled surgeon and social justice activist. The foundation performs vision-saving catarsurgeries all over the world, and Atlantic supports its work in South Africa and Viet Nam.

Here in Queenstown, the South African Government provided the funds for construction of the first-class Sabona Vision Centre, and Atlantic funds, through Fred Hollows, provided the equipment. Though I am a bit squeamish about such things, I donned medical scrubs and, along with Jack, went into the operating theatre to watch a cataract operation up close. In the developed world, we tend to take it for granted that if we develop cataracts – as most people do if they live long enough – we can get it taken care of in what is a low-risk, outpatient procedure. Not so for the poor. Poor people are both more likely to develop cataracts because of bad nutrition and environmental factors, and more likely to suffer economic devastation if an elder or breadwinner can no longer see. Sabona performs about 2,500 such operations a year, a 62 per cent increase since our funding began.

After a break for tea, we met in the same room with officials of Lilitha College of Nursing, led by the lively Homba “Matilda” Mbole. Lilitha received a capacity-building grant from Atlantic as part of our initiative to improve the training of nurses, critical front-line workers in the country’s efforts to improve health. Lilitha, with satellite campuses in five other parts of the Eastern Cape, produces about 500 nurses a year, all of whom pledge to give at least four years of service to their home communities.

It’s always inspiring to get into the field to meet Atlantic grantees, everywhere in the world – people like Patrick Pringle, Mary Hlalale and Homba Mbole, who despite other opportunities for more lucrative or comfortable work, choose to spend their lives devoted to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people and the communities in which they live.

Win-Win-Win-Win

Posted by Jack Rosenthal | 17 March 2011, South Africa

The size of this country became palpably clear today. There’s not one Cape Province but three, and we spent some seven hours all told going from Cape Town in the Western Cape to and through the Eastern, covering probably 800 miles (1,287 kilometres). The plane part went fast. Then we drove, and drove, through vast empty, scrubby plains with occasional cattle as the only signs of life, and with three, four, five receding lines of hills on the horizon. So it was striking suddenly to arrive in the quaint college town of Grahamstown. It’s the home of Rhodes University, begun in 1906 by, yes, that Rhodes, and until only a few years ago, it was a decidedly all-white institution.

One would never know that today. At a welcoming lunch, Saleem Badat, the Vice Chancellor, told us that now, 58 per cent of the 7,000 students are black, including many from other provinces and countries, attesting to the strength, even fame of several faculties. One of the leading ones is the School of Journalism, which, with 700 students, is probably the largest in the country, perhaps all Africa. Its modern building is rimmed, strikingly, by a flashing news zipper, like the one in Times Square in New York.

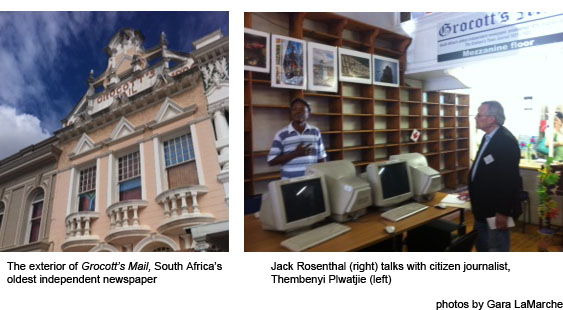

What may be the most distinctive feature of the school, however, is located a couple of miles away, in the Victorian town centre. It is a unique institution for which University officials express profuse gratitude to Atlantic. It’s called Grocott’s Mail, a local newspaper that traces its roots back to the 1830s. Nine years ago, still run by Grocott family members, it was about to fold, or be sold to a big chain. That’s when the University stepped in, armed with ZAR5 million from Atlantic.

The paper was not only saved but has become an exemplar of how to teach journalism. Each term, 60 or 70 students work with the full-time staff to write, edit, illustrate and produce the twice-weekly paper, both in print and online. And that’s only the first of three wins. The second win is that, since the University’s purchase of the paper, it has expanded its reach, from a largely white middle-class audience. The staff prides itself on covering the entire community. Beyond all that, the paper is self-sustaining. Between subscriptions and advertising, it actually earns a little profit.

There’s actually an associated fourth win. The journalism school conducts several other programmes in the Grocott’s building, like an independent quarterly student newspaper. More dramatic is a programme that has been sponsored by the Knight Foundation, to teach citizen journalism. Probably 200 residents have taken the course over the last 18 months, people like Thembenyi Plwatjie who comes in almost every day. It doesn’t hurt that citizen journalists are paid ZAR100 (about $15) for each story published in the Mail. But Thembenyi has developed a crusading reporter’s spirit. He’s proud, for example, of writing about a neighbourhood where toilets had not worked for two years. His story prompted the municipality to instantly install portable facilities.

We ended a long day with a long drive to Queenstown, arriving in the dark with heavy rain and, sigh, a power failure. It looked like a ghost town and when we finally stumbled our way to the guest house and sat down in the ornate public rooms, it felt like Colonel Mustard in the Library. Sagging spirits revived after a home-cooked dinner and when we got back, hallelujah, the lights were on.

Shadows, Then and Now

Posted by Jack Rosenthal | 17 March 2011, South Africa

Then: Faded signs on two weathered wooden benches flanking the doors to the venerable Cape Town Chamber of Commerce at 40 Queen Victoria Street: Whites Only and Non-Whites Only.

Now: Huge tan billboard on Eastern Boulevard, facing Adderly Street, a main shopping street:

Famous Last Words

“We Were Drunk”

Use a Condom

Then: The University of the Western Cape (UWC) started as an all-coloured college, so troubled and underfunded that it was said to be near collapse.

Now: In good measure because of Atlantic, the UWC we visited today is an expansive and expanding campus of glass, steel and 19,000 students of all races with schools or departments or centres covering astrophysics, museum and heritage studies, community law, humanities, biotechnology and (boy do people here love abbreviations and acronyms) PLAAS, the Poverty, Land an Agrarian Studies.

Atlantic is one huge reason for the transformation into one of the best universities on the continent, no longer so deferential to the distinguished, formerly all-white University of Cape Town. Atlantic has spent more than ZAR200 million to create the huge new Life Sciences Building, the nearly as huge new Public Health building and a nursing programme.

The second huge reason for the transformation is Brian O’Connell, the Vice Chancellor, the head man by South African protocol; the position of Chancellor is honorary, customarily held by, for instance, Bishop Tutu, who is just leaving this post here. O’Connell, who came ten years ago, is a remarkable enthusiast who makes stories of progress contagious rather than bragging. As Zola Madikizela, our health expert from the Johannesburg office, observed, “Brian is a living demonstration of the power of leadership.”

He’s also clear. Why are South Africans of all races sour about the government? Because, under apartheid, income broke down roughly this way: whites had 5, coloured had 2 and blacks had 1. Now that government spending has to be much fairer, and considering the much higher number of blacks, the figures come out more or less: 1.5, 1.5 and 1.5. That means whites lost much, coloured lost some and blacks gained only a little, much less than they had expected.

The Public Health staff, in our next meeting, reviewed their programmes, largely Atlantic-sponsored, in teaching, research and outreach. They include a year-old Centre for Research in HIV and AIDS that will supplement other national programmes mobilised to deal with this pandemic.

That was a sub-theme of our next visit, with the Minister of Health, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi. Soon after entering his immaculate seven-window office, furnished with five white arm chairs and a white sofa, we came to understand why he is so highly regarded by our grantees. He quickly explained why the health system desperately needs to be re-engineered and outlined how. The present system spends far more than the results justify, he said, making us think parallel thoughts about the American system.

A couple of his points: Each of the country’s 52 health districts must have a gynecologist; maternal death rates are unconscionably high. . . and there are some 65,000 health care workers who are redundant, overlapping, indifferent or incompetent. From them, he said, “we get nothing . . . no clear outcomes.” And most important, school health programmes must be improved, dealing with teen pregnancy, HIV and drugs. For too long, the Ministry’s response has been flavour of the month, faddish. “Hit and run,” said his assistant. “Better,” he interrupted, “to say ‘hit and miss.’”

Leaders Equal to the Challenges of the Moment

Posted by Gara LaMarche | 16 March 2011, South Africa

These days in South Africa are not meant to have a theme, necessarily, but if today had one it would be how remarkably fortunate the country has been to have first-rate leadership at critical moments in its history. Nelson Mandela is the most shining example, but there are many others.

I started with a short breakfast at our hotel with Shelagh Gastrow, founder and director of Inyathelo, a key Atlantic grantee that assists nonprofits with capacity building and also works to promote philanthropy in South Africa, a country with much new wealth that is yet insufficiently tapped for civil society support. She brought me up to date on a new network of donors that is a very encouraging development.

I joined the others in our entourage — which includes, in addition to Jack and me, the four most senior programme staff in Atlantic’s South Africa office: Nobayeni Dladla, the country director; Gerald Kraak, Reconciliation & Human Rights programme executive; Zola Madikizela, Population Health programme executive; and Oluseyi Oyedele, Strategic Learning programme executive – on a quick visit to the Visual History Archives, an Atlantic grantee that is about to launch a terrific online compendium, complete with the latest in mapping technology of documents, photos and videos of the anti-apartheid struggle. We got a great demonstration of the site only hours after all the bugs had finally been fixed.

Next stop was Milnerton, a Cape Town neighbourhood right on the ocean, to see Bishop Desmond Tutu, a moral icon for the world who came to prominence as a powerful moral voice against apartheid, but who remains the conscience of the country and a clarion on many issues, from gay rights to xenophobia. We were at this point early, having overestimated the traffic, so we stopped off at the beach for 20 minutes, a welcome dose of sun after the kind of winter we’ve had in New York.

The Bishop’s office – actually, the office of the Desmond Tutu Peace Foundation — turned out to be in a kind of business park that could not have been more nondescript and ordinary – right above a printers’ supply shop and a few doors down from an auto parts store. That lack of pretence was in keeping with the hour we spent with the Bishop, starting with a short prayer and full of (mostly self-deprecating) laughter. He is eager to see more South Africans step up their philanthropy (“I know we are a more compassionate country.”) and troubled by the continuing failures of a rich country to do more for the poor majority (“It is unconscionable that we can build world-class stadiums but not house all our people.”) We left feeling blessed, as indeed the country has been, by his generosity of time, voice and spirit.

On to the University of the Western Cape, a historically coloured university that not so long ago was slated for closure, but which has been transformed by Atlantic support starting in 2005. Over lunch in the brand-new Life Sciences Building constructed with Atlantic support, the dynamic Rector of UWC, Brian O’Connell, told the story of how Atlantic Founder Chuck Feeney’s vision turned the university’s fortunes around. Chuck’s prediction that Atlantic support would leverage other funds, not just for UWC but for other South African institutions, proved to be true: the South African Government now commits ZAR7 billion to higher education. UWC itself has grown from 12,000 to 19,000 students; is among the seven top-ranked universities on the African continent; just graduated 200 new nurses; and supplies almost 50 per cent of all new dentists in the country. UWC was a classic underdog institution – both under-resourced and serving students who have not traditionally had access to higher education. Now it is joining the first ranks, succeeding in a mission that could not be more vital to the future of the nation.

We ended the afternoon with a visit to the Houses of Parliament to talk with Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, appointed Minister of Health by President Zuma in 2009. The contrast with the head-in-the-sand policies of the previous administration could not be more stark, and emblematic of this change was the fact that the magazine of our grantee, Treatment Action Campaign – ferocious critics of the Mbeki Administration’s policies – was on the table in the Minister’s waiting room. By his own account, Dr. Motsoaledi is undertaking a “massive re-engineering” of the South African health system, and in our focus on systemic issues like the management of district health systems – vital building blocks in the nation’s health delivery – and training of nurses. Atlantic is pleased to have, at last, a strong partner at the highest levels of government.

In Bishop Tutu, who inspired a nation struggling for rebirth; Brian O’Connell, a change agent for those too-long left out of higher education; and Aaron Motsoaledi , transforming a key ministry essential to the realisation of South Africa’s democratic vision; in these and so many less celebrated leaders we have had the privilege to meet, we see how this amazing country has had the incredible fortune to find leaders worthy of its people and its promise.

Out of the Shadows

Posted by Jack Rosenthal | 16 March 2011, South Africa

The Vineyard Hotel spreads out gracefully in the shadow of Table Mountain, with a seductive garden and ponds. It began in 1800 as the first town house on the Cape. Now, with its new wing, done in glass, Scandinavian woods and extensive art, it typifies the Cape Town we traversed repeatedly on our fourth day. Again and again, we saw the new emerging from the shadows of the past.

My day began at breakfast with Dr. Alison Gillwald, who runs an organisation, sponsored by a Canadian agency similar to USAID. Its mission is to help bring the Internet to African countries, at first 18 and now, with budget cuts, 10. Wired broadband Internet service is still in its infancy here but she estimates that 70 per cent of the population has mobile phones, potentially Internet-capable smart phones. She described one project that makes eminent good sense. The government regulatory agency lacks staff with skills; she aims to develop training both for technical and policy capabilities.

By contrast, our next stop demonstrated state-of-the-art digital technology, the Visual History Archive. There, Craig Matthew, a TV cameraman whose career took him through the drama of the 80s and early 90s, and his colleagues have just finished – yesterday – innovative software that mashes data, documents and visuals of the long march to freedom, with Google Maps. After some trial runs, they intend to make it available to the world, free for low resolution, at a fee for commercial users.

We were startled by the nature and clarity of detail, like a journal, of the mail sent and received by Nelson Mandela while in prison, in his own hand. And, speaking of Robben Island, we stumbled on a brownish map of the Island in the 1880s, when it was a leper colony, men on one side, women on the other. Before our next appointment, we had a few minutes to kill so we stopped at the beach, from which we could see, on the horizon, Robben Island.

We went on to living history, a meeting with Bishop Desmond Tutu at his Peace Centre, which started somewhat inauspiciously. It is located in a strip mall, next to the Crossbow Marketing Company. But once inside, we were quickly enveloped in an amiable welcome and had only a few minutes to look around, for instance at a poster of ads for his Children of God, A Storybook Bible in English, and also in half a dozen other languages, including Bantwana BakaNkulunkulu, the Zulu version.

He came out laughing to greet us, in white short-sleeved shirt, gold tie and beaded bracelet reading “Ubuntu.” He looked as though he had more pounds and much less hair than we remembered. He turns 80 next month but seems fit and wholly cheerful; he has a way of eliciting laughter from even a passing remark. For instance, he said with a trace of affected guilt, he’s just back from a trip to . . . Las Vegas! And on the same trip he had stayed with the Omidyars, founder of eBay, in an estate whose size amazed him.

“Americans,” he said, “are wonderfully generous. It seems to be built into their genes. People in other countries are not like that.” Bishop Tutu said he very much hopes the same spirit of generosity can be developed in South Africa – hope being something different from optimism, which is shallow. Later, he continued the thought, saying it is unconscionable for South Africa to tolerate so much hunger, so much poor housing. He does not criticise the black “nouveau riche,” with their big houses and fancy cars. Blacks have been down so long that it’s understandable for them to want to show they have made it. But how could the country spend ZAR100 million for an international youth jamboree last winter when so many are hungry. “We have the resources. Why can’t we use them wisely?” He’s an old man, he said, ready to step off the stage, but is encouraged by the optimism of the young leaders he sees around.

Razaan Bailey, his youngish assistant, told us about some of their causes, including harsh school policies, so close to our Children & Youth Programme cause that she expects to visit Atlantic when they’re next in New York.

Updates from Grantees on National Issues

Posted by Gara LaMarche | 15 March 2011, South Africa

Today, our final day in Johannesburg, was devoted mostly to roundtables with Atlantic grantees and consultants at our Rosebank office to give us a chance to dive deeper into some key national issues. In the morning, a discussion of the current state of civil society, a broad topic, and the grantee presenters–from the Legal Resources Centre, the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI), Section 27 (formerly the AIDS Law Project, now renamed after the provision of the South African Constitution dealing with social and economic rights), the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution–honed in on health and other social rights, reminding us that police killings, efforts to rein in the media, and other violations of civil and political rights remain a serious concern.

Atlantic has long supported the Treatment Action Campaign, the grassroots organisation whose aggressive, in-your-face activism was critical in forcing the South African Government to provide access to lifesaving antiretroviral drugs and abandon the Mbeki Government’s benighted policy of AIDS denialism. Now, under the Government led by Jacob Zuma, with its progressive Health Minister, Aaron Motsoaledi (who we’re set to meet in Cape Town tomorrow), there is more space, according to Section 27’s Jonathan Berger, for a “multiplicity of voices.” TAC and Section 27 find themselves working closely with the government to assure proper implementation of policies, a shift from their traditional adversarial stance. “We banged on the door for years, now that it’s open, we’re going to come in,” said Nonkosi Thumalo, TAC’s Chairperson. And yet, realising the dangers of co-optation, the groups strive to stay accountable to the poor and marginalised South Africans who rely on them to be ready to act in opposition if necessary.

Beyond health, the civil society groups that came to meet with us collaborate closely with one another and often share common officers. They concentrate on holding government accountable to the promises made in one of the world’s most far-reaching and human rights-protective constitutions.

“The rights are there,” Jackie Dugard of SERI told us, “they look lovely,” but “at the grassroots people are sick of promises.” This has given rise to hundreds of spontaneous “popcorn protests” in informal settlements over service delivery failures–electricity, water, housing and food–not to mention the 40 per cent unemployment rate.

Later, a panel of journalists and free expression advocates filled us in on the state of recent efforts by the ruling African National Congress to curb the press through a government media appeals tribunal and to “protect” sensitive government information through an extremely broad proposal that would cover universities, businesses, and even museums and zoos. The first seems to have been abandoned in favour of “voluntary regulation,” and the second sharply narrowed after civil society rose up in an outcry. But the government’s impulse to punish the messenger and the critic is deeply worrisome.

We closed the afternoon with presentations by three Atlantic consultants working together to assess the feasibility of launching a community foundation on lesbian and gay issues. Atlantic has been supporting LGBT advocacy for a number of years in South Africa. In this realm, as in the issues we discussed earlier in the day, there is a gap between a visionary and protective constitution and the realities on the ground, where homophobic violence is rampant and often unaddressed. As we plan to exit the field–and, because Atlantic is a limited-life foundation that will stop making grants entirely in 2016,–sustaining key organisations and movements are paramount concerns. Leaving a strong local foundation behind–supported by other foundation partners, concerned businesses and individual donors–would be a powerful way to assure a legacy, and we are exploring it seriously.

Unity

Posted by Jack Rosenthal | 14 March 2011, South Africa

The most surprising discovery to a first-time visitor has dawned slowly: unity. In one setting after another, business or social, we’re seeing South Africans of all races talking, walking, laughing and working together in what to a newcomer’s eye looks wholly unselfconscious, natural. For sure there is widespread residential separation and these are superficial impressions of barely 48 hours. Still, day-to-day relations seem entirely comfortable. Blacks, whites, coloured all shop at Woolworth’s, which here is a mid-priced department store. They mingle easily in restaurants and cocktail bars. People sit next to each other on the new Gautrain (Gau-gold) rapid transit train seemingly oblivious to race.

There are surely strong reasons for this ease, probably starting with the extraordinary example of Nelson Mandela. It has been intensified with conscious effort, like the 2009 World Cup here, with its enduring monument, the huge, red-orange, tubular “calabash” stadium, we saw yesterday. Unity also is reflected in the tolerance of South Africans from many black backgrounds, at least in Johannesburg, who speak nine different native languages like Zulu and Xhosa (pronounced click-cho-sa) and Afrikaans and English. And that doesn’t take into account the Africans we’ve encountered from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya and other countries.

We found a pronounced example of such easy relationships on our three-hour visit to a major Atlantic grantee, the School of Public Health at Witwatersrand University, one of the leading universities in the country. Six officials and faculty members – white, black and coloured — gave us an extensive briefing, over saran-wrapped salads. I was struck by two programmes in particular, paraprofessionals and construction.

The first involves the creation of a programme to train clinical associates, skilled health care providers who go through a three-year training programme. There were 24 in the first class; this year’s incoming class has grown to 54. Graduates will work all over the country, notably in rural clinics urgently in need of help.

Then we were taken through hallways crowded with tiny offices, to peek outside at a wide green swath that is the cleared site for a new building to house all the School of Public Health. The school now spills over into several floors and buildings, and the staff can’t wait for the expected 16 months until the new home is finished. It will cost ZAR140 million ($20 million plus) and they are especially grateful to Atlantic for having provided the ZAR20 million it took to close the fund drive.

As we exited, we were led through a touching little medical museum, including a reconstruction of a 19th century Apotheker’s Shop and a room containing spacesuit-like devices that astounded younger members of our group. They had never before heard of iron lungs, vestiges of a polio epidemic in East Rand in the 1950s.

The day ended, on a graceful note of unity, as we joined with funders, black and white, in a reception at a Greek restaurant. The animated conversation about the need for better public schools and the cost of private schools could as easily have taken place in New York. That topic foreshadowed a strong topic of discussion upcoming tomorrow: delivery of public services.

Contrasts

Posted by Jack Rosenthal | 13 March 2011, South Africa

Contrasts: Our evening at the Gaults added a dimension to the afternoon “experience” in Soweto. They live in Westcliff, a leafy hillside neighbourhood of large homes with park-like gardens; it looks very much like Rockingham Drive in Beverly Hills. We were informed that the income gap between rich and poor in South Africa is greater than anywhere else and we saw that divide just in Soweto. The very name, an acronym for Southwest Township, has become a global synonym for packed, miserable hovels. But the reality belies the stereotype.

Yes, there are thousands of tin shacks, with rocks to hold down the corrugated roofs (and old tires, too, to deter lightning). Yes, there are children playing in crooked muddy lanes between shacks. Yes, there is the occasional horse and wagon clopping along on the modern highway. But it seemed as though for every slum neighbourhood, there is another, pastel tile roofs, small gardens and two-car garages, evidence of the rapid emergence of the black middle class.

In our drive around one such section, Diepkloof, we learned that it itself is divided, in popular argot, between Diepkloof Expensive and Diepkloof Extended. In the first, we saw brick and stucco houses, ornamental gates with heraldic shields, Toyota Corollas and security signs warning “Narmin GC Chubb: Armed Response!” House prices now range from zero for squatter shacks lacking doors to as much as ZAR1 million, about ZAR7 to the dollar. Petrol costs ZAR9.27 per liter: I calculate that’s equivalent to $5.01 per gallon.

We were told that crime, abating somewhat, continues to elicit constant vigilance. The wave of carjackings has tapered off but there may be a rise in home invasions. Between cocktails in their garden and dinner inside, the Gaults locked the glass doors. Mandela now lives in the old prestige neighbourhood of Houghton but even there, our guide reported, his home is protected not just by a wall but also by laser beams.

Yet for all the rich-poor contrasts, my most striking first impression – about which more tomorrow – was unity.

Greetings from South Africa

Posted by Gara LaMarche | 13 March 2011, South Africa

Greetings from South Africa, where I am spending the week visiting Atlantic’s country office here in Johannesburg and travelling around the country to meet new grantees, get updates from existing ones, and enrich my knowledge of the country’s political and social situation. I’m accompanied by Jack Rosenthal, Atlantic’s New York-based Senior Fellow, and we’ll be posting every day this week about what we’ve seen and heard.

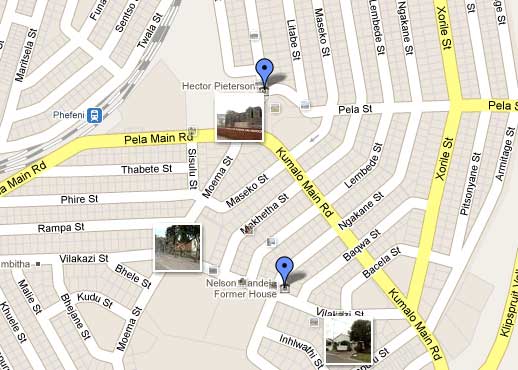

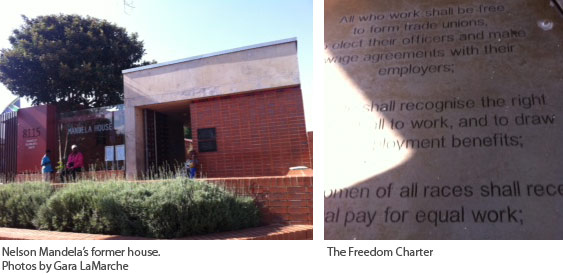

After resting up from our 16-hour flight from New York (we arrived Sunday morning), we went on a tour – our young guide, Thabo, preferred to call it an “experience” – of Soweto, the collection of 35 townships southwest of Johannesburg, where key events in the nation’s freedom struggle took place. We visited the memorial to Hector Pieterson, the 13-year old killed in 1976 when security forces opened fire on protesting students, and Walter Sisulu Freedom Square in the Kliptown section, where 3,000 people gathered to adopt the Freedom Charter in 1955, which was the basis of what is now the South African Constitution. And we stopped by Vilakazi Street, where Nelson Mandela lived before his lengthy imprisonment, just up the road from Desmond Tutu – perhaps the only street in the world that was home to two Nobel Laureates.

It’s always important, when visiting South Africa, to be grounded in the history of resistance that transformed the country from a racist, violent, oppressive state to one of the world’s beacons of freedom with the democratic elections that made Nelson Mandela the president in 1994. That’s less than 20 years ago – and around the time that The Atlantic Philanthropies, then still an anonymous donor – began its philanthropic activity here. Much contemporary commentary on South Africa focuses on the large challenges the country faces – poverty and inequality, AIDS, xenophobia, crime – but it’s vital to recall how far the nation has travelled to make good on its democratic promise.

When Jack was in the U.S. Justice Department in the Robert Kennedy era, he met the young Charlayne Hunter, who bravely tried to integrate the University of Georgia. As Charlayne Hunter-Gault, she went on to a distinguished career in journalism at The New York Times (where Jack was editor of the Magazine and editorial page), CNN, PBS and NPR. She now spends much of the year in Johannesburg, where she and her husband Ron, a banker, also operate a wine business, Passages. We had dinner with them last night after getting back from Soweto, and I’ll let Jack take over from here.