It’s Time to End Zero Tolerance in Schools: A Call To Action

Resource type: News

Gara LaMarche |

It is too early to know whether the current wave of school reforms in the United States will lead to lasting improvements in student achievement. But it is not too early to note that many of these reforms have a troubling consequence: a doubling-down on harsh, ineffective zero-tolerance discipline policies. All too often, the debate about school reform has wrongly emphasised pushing troubled children out of school, rather than making systemic improvements so that all students have the support they need to learn.

It is too early to know whether the current wave of school reforms in the United States will lead to lasting improvements in student achievement. But it is not too early to note that many of these reforms have a troubling consequence: a doubling-down on harsh, ineffective zero-tolerance discipline policies. All too often, the debate about school reform has wrongly emphasised pushing troubled children out of school, rather than making systemic improvements so that all students have the support they need to learn.

For that reason, Atlantic supports advocates throughout the U.S. who seek to improve school climate. School leaders are recognising the ineffectiveness of zero tolerance. And as states grapple with untenable youth-prison budgets and Congress prepares to debate reauthorisation of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), a movement is building to end the ineffective, expensive and tragic era of zero tolerance.

Throughout the U.S., suspension and expulsion rates are at crisis levels. The most recent data from the National Center on Education Statistics (NCES) showed that more than 3.3 million students were suspended or expelled in 2006—nearly 1 in 14. Of those, fewer than one in 10 were for violent offenses. The vast majority were for vague, noncriminal offenses, such as tardiness, talking back to a teacher or violating dress codes.

For students of colour, the crisis is even more extreme: In 2006, about 15 per cent of black students were suspended, compared with 7 per cent of Hispanic students and 5 per cent of white students, according to NCES data. That year, about 0.5 per cent of blacks were expelled from school, compared with 0.2 per cent of Hispanic students and 0.1 per cent of white students.

Many of these suspensions are the result of excessively punitive discipline policies. Mirroring tactics used in the adult criminal-justice system and the “war on drugs,” many school districts embraced practices that emphasise the long-term exclusion of students who violate school rules. Schools are relying more and more on the police and juvenile courts to address school-based behaviour that used to be handled by educators.

Learn more about Christopher’s story in the “Zero Tolerance in Philadelphia” report.

In New York City, a recent analysis by the New York Civil Liberties Union revealed that suspensions of 4- to 10-year-olds have increased 76 per cent since 2003.

In Colorado, two friends horsing around dented a locker and were charged with felony mischief and third-degree assault, according to the Washington-based Advancement Project, an Atlantic grantee.

In Virginia, a plastic pellet spit through a straw led to assault charges and expulsion, The Washington Post reported.

In a zero-tolerance school, that’s it.

Sadly, zero-tolerance policies are as ineffective as they are prevalent. Research shows that they fail to improve student behaviour. Even worse, these policies deny students access to desperately needed services, while dramatically increasing the likelihood of future involvement with the juvenile-justice system—especially for students of colour.

This is what’s known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The United States now has the world’s highest incarceration rate, and the number of juveniles in detention has swelled in recent decades. In the United States, more black men ages 18 to 24 live in prison cells than college dorm rooms, according to U.S. Census data.

Nationwide, some districts are implementing positive preventative approaches to school discipline. The programmes vary, but all are based on similar principles:

• Creating respectful and welcoming school environments;

• Teaching positive behaviour skills and conflict resolution; and

• Expanding access to academic and counseling services for children and families.

These programmes equip students with essential skills, reducing their chances of entering the juvenile-justice system. And they cost less to implement than the cost of incarcerating a child in a juvenile-detention facility. Perhaps most importantly, these programmes help all children learn better, not just the ones who may be struggling in school.

In Baltimore, a focus on positive discipline helped improve attendance and achievement rates among black males most at risk of dropping out. In Indiana and Louisiana, two states plagued by notoriously violent youth-prison systems, a shift is under way to discourage suspensions and expulsions. In Clayton County, Georgia, and Birmingham, Alabama, family-court judges led efforts to establish protocols between schools, law enforcement and local service agencies that improved school attendance and decreased school-based referrals to the courts. This trend is promising.

This year, Congress is likely to take up the reauthorisation of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the federal government’s main vehicle for helping to fund K-12 public education. The Obama administration’s blueprint for the ESEA, which the president laid out last year, maintains an emphasis on testing in promoting school accountability.

On the one hand, standardised testing seems to have exposed the poor quality of education in many American schools and the urgent need for reform. But the increasing pressure to raise test scores also has encouraged the practice of pushing “problem” children out of school. This is not the fault of educators—it is the product of a set of systemic incentives.

The reauthorisation of the ESEA is a critical moment for discipline reform. Abolishing zero tolerance is essential to closing the door on the school-to-prison pipeline, and creates an opportunity for a frank national conversation about what schools can and should be doing to support achievement—especially for children of colour.

At the state level, the budget crises gripping governments have led to reform. In New York and California, new governors are pledging to shut most youth prisons, investing instead in more effective alternatives that will reduce school-based arrests and referrals into the juvenile-justice system.

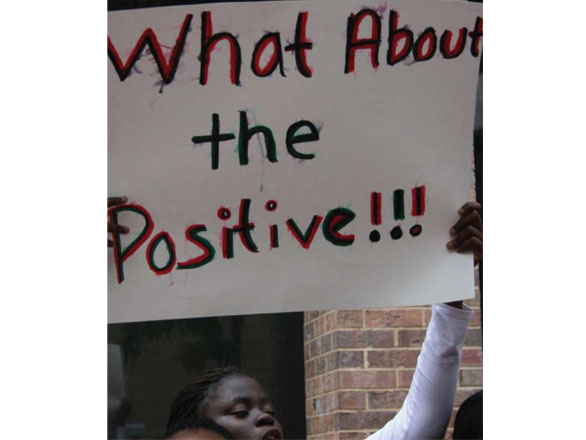

![]() At the local level, students and parents are coming together to demand an end to zero tolerance. A recent report, “Zero Tolerance in Philadelphia,” was produced by the student-led Youth United for Change and the Advancement Project, both Atlantic grantees. The report received significant national media attention, and many observers said they were inspired by the students’ passion to advocate on their own behalf.

At the local level, students and parents are coming together to demand an end to zero tolerance. A recent report, “Zero Tolerance in Philadelphia,” was produced by the student-led Youth United for Change and the Advancement Project, both Atlantic grantees. The report received significant national media attention, and many observers said they were inspired by the students’ passion to advocate on their own behalf.

These efforts are supported by national advocacy organisations, including grantees like the Dignity in Schools coalition, the Alliance for Educational Justice and the Advancement Project, which are calling for federal action to improve discipline data collection and monitoring and to provide resources to help districts adopt more effective strategies for improving discipline.

Atlantic is investing in this national push for positive discipline alternatives by promoting federal advocacy while supporting efforts such as those in Philadelphia, where the people most affected are organising against zero tolerance. Through the Just and Fair Schools Fund at the New York-based nonprofit Public Interest Projects, we now fund 21 grassroots organising groups that are working to improve discipline practices in 14 states.

Our long-term goals are to reduce expulsion and suspension rates, raise achievement and dramatically reduce the pernicious disparities affecting students of colour. We hope our support will inspire other funders to step forward at this critical moment.

Nearly 10 years ago, to deepen my understanding of criminal justice reform, I spent a summer sabbatical volunteering at a re-entry programme for returning prisoners. What struck me is that not one of these men and women had finished high school—a critical turning point in their path toward prison—and they had to fight to make up that learning deficit once behind bars. We have to do everything we can to make sure young people at risk are not pushed out of school and into the criminal justice system.

Our hope is that starting now—with the ESEA reauthorisation, budget cuts and burgeoning activism unfolding in front of us—philanthropists, educators and policymakers will come together to end these ineffective, expensive and morally corrupt policies, and work to create safe and positive climates in schools that give every student a fair chance to learn.

This piece is adapted from an op-ed by Gara LaMarche which ran in Education Week on 06 April 2011.

Photos provided by Youth United for Change.