L.A. Schools Moving Away From Zero Tolerance Policies

Resource type: News

Los Angeles Times | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

Students, parents and teachers staged a rally last month in front of the L.A. Unified Schools headquarters to urge the district and School Police Department to overhaul its old system of citations for students committing minor offenses. (Gary Friedman, Los Angeles Times / August 9, 2012)

By Teresa Watanabe

Josh Garcia got his first police citation in sixth grade for spray-painting graffiti at his middle school. Then came four more tickets for truancy and violating curfew.

The worst was at Roosevelt High in Boyle Heights, where he got caught with brass knuckles and was sentenced to weekend detention in Central Juvenile Hall — a scary experience, he said.

By senior year, Garcia had had so many run-ins with the law and fallen so far behind in school that he failed to pass the high school exit exam or earn enough credits to graduate. He dropped out.

But a new partnership among Los Angeles city, police and school officials aims to support — rather than punish — students like Garcia before it’s too late. In a decisive step away from the zero tolerance policies of the 1990s, Los Angeles school police have agreed to stop issuing citations to truant students and instead refer them to city youth centers for educational counseling and other services to help address their academic struggles.

A new approach is also in the works at the Los Angeles County Probation Department. Officials there are launching alternative programs to keep students out of the court system and provide them instead with counseling, tutoring and other community services.

A new approach is also in the works at the Los Angeles County Probation Department. Officials there are launching alternative programs to keep students out of the court system and provide them instead with counseling, tutoring and other community services.

The move away from punitive law enforcement actions and toward support services reflects a growing awareness, grounded in research, that treating minor offenses with police actions did not necessarily make campuses safer or students more accountable. Instead, officials and activists say, it often alienated struggling students from school, pushing some to drop out and get in more serious trouble with the law.

The shift is being directed by new city and county leaders who community groups say are far more responsive to the groups’ long-running complaints. L.A. Unified Schools Supt. John Deasy, school Police Chief Steven Zipperman and L.A. County Chief Probation Officer Jerry E. Powers — who all took office last year — have embraced the changes for low-level student offenses.

“There’s a very big pendulum shift,” said Robert Sainz, assistant general manager of L.A.’s Community Development Department, which is working with L.A. Unified. “This is the first time the city and school district are working together specifically to bring students back to school.”

Community groups have tried to change police citation practices for at least seven years. After years of requests, they finally obtained school police data this year showing that more than 33,800 citations were issued from 2009 to 2011 — some to students as young as 7. The majority were for truancy, disturbing the peace and tobacco possession.

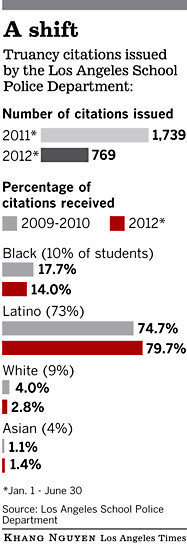

In what advocates called an alarming indication of racial disparity, African American students received 18% of citations although they make up just 10% of L.A. Unified’s enrollment, according to an analysis by the Labor/Community Strategy Center, a Los Angeles-based civil rights group.

But under a policy Zipperman issued in October, school police have refrained from issuing truancy tickets to students on their way to campus during the first 90 minutes of school — reducing the number of those citations 55% in the first six months of this year compared with the same period last year. Citations to African Americans decreased 68% between 2009 and 2011 and to Latinos by nearly 40% in the same period. And the racial disparity, although still present, is narrowing, with 14% of tickets now going to black students, Zipperman said.

Some citations carried hefty fines of more than $250, which many low-income families couldn’t pay, and required students to miss school and parents to leave work to appear in court, according to Zoe Rawson, a lawyer with the labor strategy center.

Kieta Perez, 16, received a citation for disturbing the peace two years ago when she got in a fight at Crenshaw High School. The ticket was eventually dismissed, but Kieta said she missed three days of school to deal with it and was never given a chance to work out tensions with the other student.

“We should be getting counseling … to find the root causes of our problems instead of getting tickets,” she said.

Rather than receiving truancy tickets, students will be directed to one of 13 youth centers, Zipperman said. There, a school district specialist will evaluate the students and connect them with services to get them back on track.

Zipperman said the program, funded with both federal and district money, should keep virtually all truant students away from the criminal justice system. A 2006 study by Gary Sweeten, an Arizona State University associate professor of criminology, found that a high school student’s first arrest and court appearance quadrupled the likelihood of dropping out of school.

“We’re looking at how we can best try to resolve truancy issues by looking at root causes of problems rather than just handing out citations,” Zipperman said. “It’s the right thing to do.”

The program initially will handle only truant students, but officials say they hope to expand it to those cited for other offenses such as fighting and tobacco possession.

Deasy said the new approach will help with his goals to increase graduation and attendance rates and with campus safety. Recently, he released a three-year strategic plan that included a commitment to using campus police in a “nonpunitive enforcement model.”

“We want to be in the business of holding students accountable for their actions but not with measures that increase early criminalization,” Deasy said.

At the Probation Department, students referred by L.A. Unified and police for such minor misdemeanors as fare evasion will no longer be formally booked into the criminal justice system, according to Hellen Carter, the new chief of the department’s juvenile field services bureau. Instead, their cases will be tracked through an internal record-keeping system so students will not have a formal court identification number that could prevent them from future academic and job opportunities, she said.

And they will be referred to community-based services, Carter said.

Community activists are pushing for even more action. The Community Rights Campaign, for one, recently held a rally at L.A. Unified’s headquarters to call for a 75% reduction in police citations and a parent-student review panel of police actions, among other things.

Still, they praise the new efforts.

“I am really hopeful,” said Laura Faer of Public Counsel Law Center, the pro bono law firm that has worked on the citation issue with community groups such as the labor strategy center and the American Civil Liberties Union. “We have a real chance to be national leaders because if we can do it with the number of kids in L.A., anyone can do it.”

Garcia, the one-time high school dropout, who is now 21 with a 3-year-old child, said he is living proof of how positive support can turn lives around.

He said a relative told him about the Boyle Heights Technology Youth Center, one of the centers that will handle truant students. There, community program specialist Maritza Sosa-Nieves helped connect him with courses in medicine and solar energy and pushed him to complete his high school degree. He is now enrolled at East Los Angeles College with an eye toward a possible career in probation work.

The difference? Not punishment, he said, but personal relationships.

“Maritza pushed me,” Garcia said. “Any problem I had, I could talk to her. It made me feel that somebody actually cared about me, and I wanted to succeed because she helped me out so much.”

The Community Rights Campaign is led by the Community Labor Strategy Center, a grantee of the Atlantic-launched Just and Fair Schools Fund. Public Counsel is an Atlantic grantee through the NAACP Legal Advocacy and Defense Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an Atlantic grantee.