The ‘Giving While Living’ Superhero

Resource type: News

Outlook Business | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

Chuck Feeney is the biggest philanthropist people know nothing about. The reclusive former billionaire not only decided to give away all his wealth in his own lifetime, but also leads a life of disarming simplicity.

By N Mahalakshmi

Therefore when thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may have glory of men. Verily I say unto you, they have their reward. But when thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth…”

— Matthew 6. 2, 6. 3, King James Bible, Cambridge Edition

Those lines from the Bible suggest that the praise people get for giving and talking about it will be their only payback. Those who do their good work quietly will get a much richer reward from the Almighty.

If there’s anyone in the philanthropic world who has adhered to those pious words — and we won’t build any suspense here because the name really will not be a give-away anyway — it is Charles ‘Chuck’ Feeney. Don’t blame yourself if you have never heard of this man. Barring an odd write-up or two over the years, he’s stayed very determinedly under the radar, despite being the founder of a multi-billion dollar company that most of us are familiar with — either as shoppers or through gifts from friends and family. At Outlook Business, too, we learnt of Feeney only about six months ago when we researched dozens of personalities across the world to build our shortlist for this special edition.

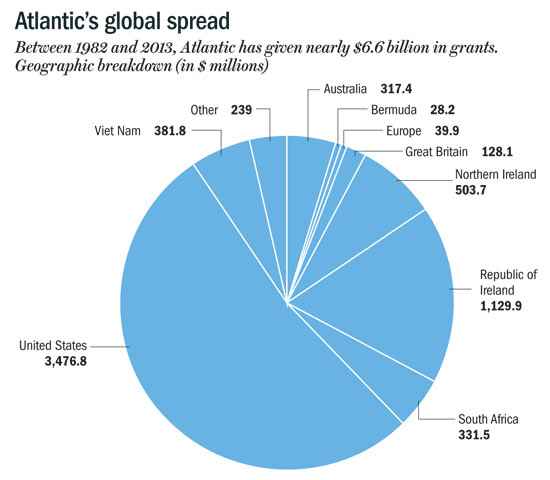

So, who is Chuck Feeney? He is the man who pursued a novel business idea, built it into an enduring company, made his billions by selling it and then chose to give away all his wealth during his own lifetime to causes that he handpicked. The company he founded was Duty Free Shoppers (DFS), which he later sold to French luxury icon Louis Vuitton. His foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, which he founded in Bermuda in 1982, has already given away $6.6 billion in supreme secrecy. It is now working overtime to write the cheques for the last billion by 2016 and will be wound up by 2020. “I would like my last cheque to bounce,” Feeney famously said. And when The Atlantic Philanthropies does wind down, it would have given away Feeney’s entire wealth to support a wide variety of causes, including education, healthcare and human rights, across several countries. No one else has ever given away their entire fortune — that too, one running into billions — while they were still alive and breathing. At 83, recovering from heart surgery, his enthusiasm for his life’s work is undimmed. “Giving while dead, you don’t feel anything,” is Feeney’s simple explanation for why he does what he does.

The Real Hero

Feeney’s idea of ‘Giving while Living’ has inspired many others, including Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. “Chuck has set an example. He’s a true innovator and example to anyone who seeks to make the world a better place,” Buffett said while presenting Feeney with the Forbes 400 Lifetime Achievement Award for Philanthropy earlier this year. “It’s a real honour to talk about a fellow who is my hero and Bill Gates’ hero. He should be everybody’s hero.” Some time ago, Bill and Melinda Gates said, “Chuck has been an inspiration to both of us for many years and was living the Giving Pledge long before we launched this project.”

What makes Feeney’s story unusual is not just the fact that he decided to give away his wealth during his lifetime, which itself is extraordinary, but how despite his billions made frugality the hallmark of his life. Feeney’s lifestyle has been quite an antithesis to the company he built, which thrived on indulging customers. He’s never owned a house — currently, he lives in a San Francisco apartment owned by his foundation. No expensive luxury timepieces for him — he wears a Casio rubber watch. Superfast cars, yachts and private jets? No way: Feeney rarely owned a car, barring a used Jaguar briefly; gets “seasick quickly”; and a private jet, he points out, won’t get him where he wants to go any faster. “He is a kind of a Franciscan figure. He is unusual because while [George] Soros and Gates give a lot of money away, they remain very wealthy. Feeney divested himself of all of his wealth. He dresses shabbily and carries his papers around in a shopping or plastic bag. If his glasses break, he takes them over to be fixed,” says Gara LaMarche, former president and CEO of The Atlantic Philanthropies, who currently serves as the president of the Democracy Alliance, a network of liberal donors who coordinate their political giving. Prior to joining The Atlantic Philanthropies, he had served as vice-president and director of US programmes for George Soros’ The Open Society Institute.

“Chuck recognises that the greatest value for money is what really matters and sometimes that value is not about having things for yourself.”

—Christopher Oechsli, President and CEO, The Atlantic Philanthropies

Feeney’s friend Niall O’Dowd, founder of news website IrishCentral, who has known Feeney for more than 25 years, says he didn’t know Feeney was rich until he was featured in Forbes as one of the richest men in the world. “That’s because he acted poor, meeting me in scrappy diners and leaving me with the check. I put up with it because he was always worth the price of the coffee and the scraped-out onion bagel. His insights were incredible,” O’Dowd wrote in his blog. He recalls a few other incidents. “Once, he took me on a long walk to a public library in Connecticut so he could pick up magazines for free there. Another time, I met him at the Merrion Hotel in Dublin, sampling the free Sunday newspapers. A few weeks later, he was up to the same trick at Fitzpatrick’s in Manhattan. ”

Feeney’s frugality doesn’t mean not spending on what he considers important. Christopher Oechsli, current CEO of The Atlantic Philanthropies, has had a 30-year association with Feeney and recalls an incident when the latter had made up his mind that he had to accelerate his philanthropic initiatives and was negotiating the sale of DFS to shore up the resource pool. Pulling through the sale was not easy as Feeney had two partners who did not share his urgency to sell and it was difficult to get a price that was acceptable to all.

As his Man Friday, Oechsli was accompanying Feeney through the two-year negotiation phase. Towards the last leg, when the discussions were getting intense, Oechsli was feeling the pressure. It was a lot of travel and he was away from home at least half the time. “I had young children, Christmas was approaching and things were getting to a crunch. I told Chuck that I would like to go visit my family.” Feeney instantly replied, “Why don’t you take the Concorde, spend the weekend and get back in two days.” Recalls Oechsli, “I said to myself, here is Chuck Feeney, who flies economy, and he is telling me to take the Concorde to spend time with my family. Chuck is not a skinflint — it is not that he does not allow people to enjoy themselves. He recognises that the greatest value for money is what really matters and sometimes that value is not about having things for yourself.”

Oechsli is one of the very few people who have had the privilege of being up close and personal with this stubbornly low-profile man. “It’s my greatest gift to have been with a man who has been there and does not believe in the primacy of material possessions for a satisfying life. He lives it; it’s not a show. It’s his recognition that you don’t need much — you can’t wear more than one pair of shoes at a time, Chuck would often say.”

Oechsli recalls his visits to Vietnam with Feeney when The Atlantic Philanthropies was actively engaged in a project there. Feeney would be completely at ease in the heat and dust of the under-developed environment and was happy staying in a $20-hotel, having basic meals — he sought neither comfort nor attention. “He would not sit behind the desk and read newspapers — he wanted to be out there wherever we were looking for opportunities. Finding opportunities to give opportunities to others was his singular obsession,” says Oechsli.

That deep-rooted desire and determination to give back is rare. But Feeney’s early years were spent in circumstances common to first-generation entrepreneurs. He comes from an underdog background, hailing from a blue-collar Irish-American family in New Jersey. As a child, he was hugely influenced by his mother, a nurse, whose work instilled in him the need to be sensitive to others. “He is always attentive, cognisant and aware of other’s needs,” says Oechsli. Growing up in an environment where people were starved of opportunities, Feeney keenly felt that opportunities lead you to use your abilities; anything that was an obstacle undervalued you as a person and was, therefore, unfair. Equity and dignity, therefore, became of utmost importance to him and creating ‘opportunities’ thus became Feeney’s main philanthropic pursuit.

Telling Tall Tales: Schoolkids in Ireland at the launch of a collection of stories on children’s rights. Atlantic has contributed greatly to children’s causes here. (Derek Speirs, Courtesy: Children’s Rights Alliance

Telling Tall Tales: Schoolkids in Ireland at the launch of a collection of stories on children’s rights. Atlantic has contributed greatly to children’s causes here. (Derek Speirs, Courtesy: Children’s Rights AllianceCreating Opportunities

Feeney has a great feel for good philanthropic investments. “Like a good entrepreneur, Chuck looks for undervalued opportunities. Where there was opportunity to invest that would create maximum uplift, he seized that,” says Oechsli. Be it going to Ireland at a time when there was a propitious opportunity to take the country to another level by investing in higher education; or investing in the healthcare sector in Vietnam; or in health science research in Australia — all decisions were made with a great sense of timing and with an intention to maximise return on investment.

“We don’t want to engage in global creep, we don’t want to be in another country just for the heck of it. Chuck had a sense that it had to be at certain opportunities, in certain locations, in certain times that can make an outsized difference on your investment return. And I have to say, he has had a pretty good track record,” Oechsli says.

Barring some high-return opportunities that were evaluated on an individual basis, The Atlantic Philanthropies has steered its efforts across two overarching themes. The first is education, where work ranges from stimulating a knowledge economy and creating libraries to supporting early childhood education. Second is healthcare, an area he probably relates to because of his mother’s influence.

As for the geographical spread, Feeney was naturally inclined to invest in creating impact in the country of his heritage, Ireland — Atlantic has invested more than a billion dollars in the country, a large part of that in education, catalysing investments from the Irish government. “There is simply no greater Irish American ever in terms of his incredible commitment to the underdog and those in need of an education. Not to mention his role in peace in Northern Ireland, where he was a significant player in the Irish-American peace delegation that got president Clinton involved,” says O’Dowd. To strengthen communities, The Atlantic Philanthropies has been supporting efforts to bring together Catholic and Protestant children and encourage shared education in Northern Ireland.

In the Republic of Ireland, Atlantic has contributed in various ways, supporting children’s causes and investing in higher education. Whether it be funding early interventions or advocacy for greater children’s rights, Atlantic has been relentless in its pursuit, with good results. Last year, citizens voted by referendum to amend the Constitution to allow for new laws to protect children. The foundation has also made a sizeable $130-million investment in early intervention programmes, recognising that parents often need support and guidance in raising children when the neighbourhood has social problems and children face emotional issues. Early interventions — such as counselling and training children and parents — cost just $950 per child, whereas later interventions could cost $352,000 over a lifetime, according to Atlantic estimates.

Atlantic has also invested significant time and resources in issues related to older citizens in both the US and Ireland. The foundation supported BenefitsCheckUp, a web-screening tool to see which programmes senior citizens are entitled to, which has resulted in 1.4 million older adults receiving more than $7.5 billion in previously unclaimed US government benefits since 2001. Similarly, the Access to Benefits project has helped more than 26,000 people in Northern Ireland collect benefits totalling $92 million since 2008.

For Life: The Atlantic Philanthropies has actively campaigned against the death penalty in the US, contributing towards its abolition in five states. (Scott Langley, Death Penalty Photography Documentary Project)

Advocacy has also been an important piece of Atlantic’s work, especially in the area of human rights. Atlantic is the largest funder of efforts to abolish the death penalty in the US, having invested $23 million in the cause since 2004. As a result, while the US Supreme Court ruled the juvenile death penalty unconstitutional in 2005, Atlantic’s numerous grantees have been instrumental in the abolition of the death penalty in five states and the prevention of another state from reinstating capital punishment.

Another area of interest is immigration reform. Oechsli narrates the story of Roberto (name changed), whom he met in Nogales, Mexico. Roberto spent 14 years in the US as a fully productive, self-employed landscaper, married a US citizen and had four daughters, all US citizens. In a twist of fate, he was arrested in a case of mistaken identity. Although he was able to establish his innocence, cops discovered a false identity card during a search and charged Roberto with two felonies. Without access to legal advice, he was deported and separated from his family. “Roberto’s crime, essentially, was to seek a better life, provide for his family and contribute to the US economy. His story reflects a broken immigration system in the US that inhibits economic development and fuels racial discrimination and fear,” says Oechsli. So far, Atlantic has invested almost $68 billion in advocacies relating to immigration reforms in the US. “We are encouraged by the building national consensus for reform and are hopeful that positive changes are on the horizon,” he adds.

Good Buildings For Good Minds

Atlantic’s strategy is very focused on the need of the hour. For example, Atlantic started working in Vietnam a few years after the war ended. Feeney started with central Vietnam, the most affected and least developed part of the country. Atlantic first funded one building for the Da Nang University, but Feeney wasn’t satisfied. He walked around the place and was struck by an old, French library building that was probably 150 sq m with just a few desks and bundles of newspapers strung together. Not much research was being done there — students would visit the library and sleep on the wooden tables because the dormitories were unlivable. While the university leadership team wanted to renovate the room and bring in new equipment, Feeney decided to take down the entire structure and build a new university block. The library there is now 30 times the size of the initial structure.

“Chuck sees opportunities quickly. Thinking big, changing the vision of what was possible, realising that you don’t have to work within the box and saying to somebody, ‘Think of where you could go and what you could achieve’ is very reflective of Chuck’s approach,” says Oechsli. Over the years, apart from investing in the healthcare system, Atlantic has spent significantly on setting up learning resource centres at key Vietnamese universities.

Repaying His Debt: Feeney’s foundation has given freely to Cornell University, his alma mater, including a $350 million grant to build a new tech campus. (Cornell University)

There’s a funny story here that Feeney recalls with a smile. After Atlantic helped build a school in Hue, Vietnam, a doctor there wanted to thank the foundation and its people for their help. “He said, ‘We’ll just make a statue or a big plaque’ and we refused. So he said, ‘Well, I have to do something.’ So, the next time someone [from the foundation] visited the school, they saw he had painted the school green. The doctor explained that, ‘Well, the people that helped us are Irish’.”

Feeney has also helped set up buildings in other countries. In 2005, he invested in a building for the University of Western Cape in South Africa after learning that researchers at this historically disadvantaged school were producing internationally-recognised work despite outdated facilities and technology. Atlantic invested a total ZAR190 million ($24 million) but there was a bigger benefit. The South African department of education ended a 15-year moratorium on spending on higher education infrastructure, matching Atlantic’s grant to the University of Western Cape, and has since given commitments of about ZAR6.9 billion ($881 million) to universities in the country.

In the US, its boldest investment — a $350 million grant to build the Cornell NYC Tech campus in Roosevelt Island — is essentially to foster innovation by recreating a Silicon Valley on the east coast. While the emotional connect with his alma mater — after serving the Air Force for four years, Feeney studied hotel management at Cornell on a military scholarship — may have played a role in giving away nearly $1 billion to Cornell, the Roosevelt campus is being built with the intention of making it a global magnet for entrepreneurship and innovation.

Then again, in the health sciences, Atlantic has funded key research and health service facilities at the Mission Bay campus of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), which houses world-class research in cancer and delivery of health services to vulnerable populations. UCSF is also a grantee and partner in delivering health services at middle schools in Oakland, California, which are associated with Atlantic’s Children and Youth programme. “Both Roosevelt Island and the Mission Bay campus of the University of California were significant locational opportunities that offered high returns,” says Oechsli.

Some other initiatives Feeney himself spearheaded include support for collaboration among Atlantic grantees to develop synergies and expand impact beyond the grantees’ institutional and geographic boundaries. The ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes for the disadvantaged, especially by supporting development of human vaccines for dengue fever, animal vaccines to prevent slaughter of herds from epidemics, establishment of advanced neurological imaging facilities and collaboration on nursing projects to tackle skills shortages. Atlantic-supported Translational Research Institute, a $330-million research facility currently under construction in Queensland, Australia, will foster the discovery, production, clinical testing and manufacture of new biopharmaceuticals. It will be the largest translational research facility in the southern hemisphere and the first of its kind in Australia.

Overall, Atlantic has spent nearly a third of its endowment, that is, roughly $2 billion, on building facilities, perhaps because Feeney understands how essential it is to have brick-and-mortar facilities to unleash talent in a place. “Chuck always uses this phrase, ‘Good buildings for good minds can make a big difference to a lot of people’. Buildings have lasting value, which is important; it’s not a flash in the pan,” says Oechsli.

No Pockets In A Shroud

No matter how fat a cheque he writes, there are no Chuck Feeney buildings or libraries or research centres or medical wings. “He jokes that it is very clever because he gets the praise for every anonymous donor these days,” says O’Dowd. “He doesn’t like to call attention to himself, which is why there are buildings and college and medical campuses all over the world that have someone else’s name on them when most of the money came from Chuck Feeney. His ethos is very strong and he really believes in what he is doing,” adds LaMarche.

LaMarche recalls accompanying Feeney to Cuba in 2007, where Atlantic has some health investments. He was pleasantly surprised to see how attentive the Cuban government was to Atlantic. “It was a new thing to me because the last time I went to Cuba, I was with Human Rights Watch and they tried to kick us out of the country.” Feeney and LaMarche had long dinners with senior officials where Feeney would sit quietly through the meals, hardly saying anything. “If it had been Soros, he would have been arguing with the officials all night,” laughs LaMarche. “He has genuine humility. Feeney prefers to be in the background, but he has strong views about philanthropy.”

Perhaps that is also the reason Feeney untiringly ensured his personal involvement in several projects. “He does not sit on his laurels or pause to celebrate them: he is on to the next thing. He gets greatest satisfaction from the chase,” says Oechsli. Feeney championed the idea of ‘Giving while Living’ only because he could be a part of the journey. “One of his most important legacies is that he has convinced so many powerful people that there are no pockets in a shroud. Helping in the here-and-now is preferable to dribs and drabs over decades,” says O’Dowd.

That’s something Feeney can say even more confidently now than 30 years ago when he started his journey. Whether it be seeing children with cleft palates transform into confident individuals after surgery (Atlantic supports Operation Smile, which provides free reconstructive surgery to children with cleft palates and other facial deformities worldwide) or watching young adults experience the mystery and wonders of the internet for the first time in libraries that Feeney funded, it is their experiences and their joy that keeps him going. “I hesitate to say this publicly, but you would see tears in Chuck’s eyes when he saw these people, although he would hide them,” says Oechsli.

Chuck Feeney has set the bar so high that most of us can only look up in awe and not even hope to emulate his life. He will go into both history and philosophy books as a man with great material means and wealth who had the potential to maintain that material standard but did not see that as being the ultimate or satisfying approach to life. He has dedicated his life to doing good for others. If he missed out on publicity for all his good deeds over the past so many decades, as the Bible says, he will get his rewards up there — in a better world. Never mind that he’s not a religious man himself.